Commentary

Terence Riley, Architect + former The Philip Johnson Curator of Architecture and Design, MoMA

“Rather than dominate the site and its surroundings, his architecture habitually seeks the contours rather than the crest. Whether the topography is dramatic or subtle, Rose’s instinct is to reinforce the geometries of the site, at times making the viewers more aware of the landscape than they might have been otherwise.”

—Foreword, Charles Rose, Architect, Princeton Architectural Press, 2006

Nancy Levinson, Architectural Record

“The Shapiro Campus Center clearly appears to be fulfilling its mandate to serve not merely as the geographic but also the functional and perceptual heart of campus. On a recent visit, the place was bustling….Administrators and students enthusiastically described how much they liked the building and how well it accommodated activities ranging from peer counseling to tango lessons. And one junior was especially effusive: ‘I practically live in this building,’ she said. Brandeis and its architect have given her a great place to live in.”

—”Shapiro Campus Center,” Architectural Record, December 2004

Randy Gragg, Editor in Chief, Portland Monthly

“Charles Rose’s studio building is, appropriately, all about energy. There’s scarcely a right angle. Walls, roofs, and even windows jut and fold, in, out, up, and down….Every corner is a carefully composed and crafted convergence of forces that turns the artmaking inside into a collaboration with the surroundings.”

Paige Williams, The New York Times

“To temper the aggressiveness of the angles made by so much glass, concrete and steel, [Charles Rose] used rich woods: mahogany to frame windows, and rosewood, mahogany and bamboo in the floors. Also, subtle colors… In this way, the house feels almost organic.”

—”Glossy Skin, Vinyl-Clad Heart,” The New York Times, December 15, 2005

Sarah Amelar, Architectural Record

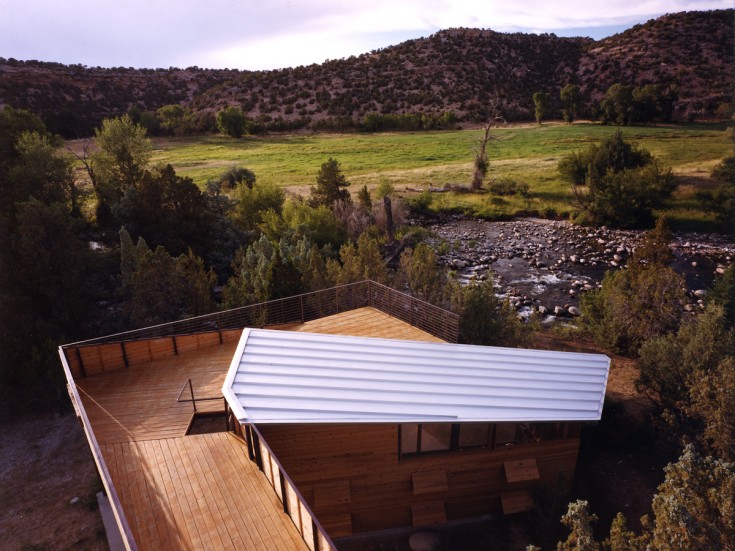

“Just as the campers use the site—its rock faces, streams, meadows, and trails—in varied ways, so too has the architect shaped and sited his buildings in response to a range of landscape conditions. The three boys’ cabins, hovering over a canyon wall, are raised on columns, carefully placed to minimize site disturbance….Large rolling screen doors and outer wooden panels open the cabins to the outside. Through roof decks, lookouts, and elevated, interconnecting walkways, the scheme offers lots of views and overviews, encouraging different ways of seeing the landscape….”

—”Camp Paintrock, Wyoming,” Architectural Record, October 2002

Marc Kristal, Dwell

“Adaptive reuse—the preservation of buildings by altering their function–has been taken to the limit in what was once a light-industrial building in Manhattan’s Chelsea district….Within, architect Charles Rose inserted a double-height retail space and, above that, an almost 5,000-square-foot private home, its C-shape surrounding—incredibly—a lawn….All views are ultra-urban yet surprisingly serene, with plenty of green to go around.”

—”Renovation Roundup: The Gift of a Garden,” Dwell, Jan/Feb 2004

Robert Campbell, The Boston Globe

“‘The spaces flow gracefully into one another, creating delightful places to be with beautiful, short-range views into adjacent spaces….The architects have created their own language that fits nicely in the Martha’s Vineyard tradition….The result is crafted extremely well, it is gorgeous, and it is organically related to the site.'”

—Juror’s comment, The Boston Globe, December 15, 2002

Ed Feiner, former Chief Architect, General Services Administration

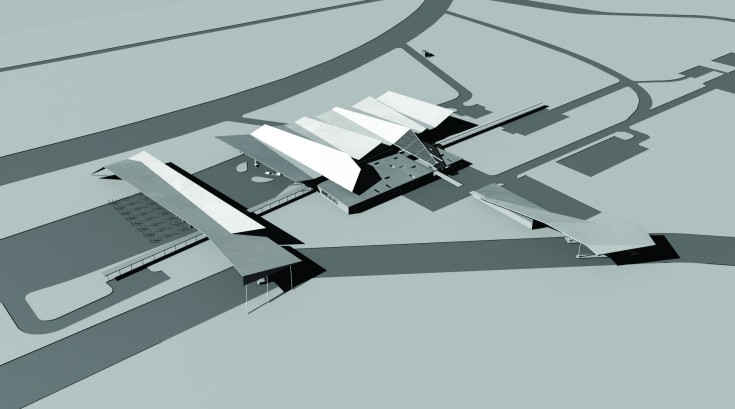

“…the southern Texas environment; and the desire to create a welcoming gateway, drove the design team to create a clear, clean, and exceedingly elegant solution. The audience appreciated the challenges of the assignment and the well-considered solution that will lead to an outstanding public building and landscape.”

Linda Lee, Editor, Princeton Architectural Press

“With surprising use of volumes, materials, and geometries, agile movement of spaces, and an active language of planes and lines, Rose creates dynamic, expressive architecture that reminds us that buildings can be both sensitive to their locale and embrace the timeless principles of geometry, material, light, and shadow.”

— Charles Rose, Architect, Princeton Architectural Press, 2006

Adam Weinberg, Director, Whitney Museum of American Art

“The siting could not be more brilliant and perfect. The views are breathtaking. The spaces are so comfortable and flowing. The sense of privacy from one bedroom to another works….The windows and light give us as close a sense of communing with nature as I would want. The fireplace is a gorgeous focal point especially at night with roaring fire in it. The kitchen is easier to work in than any we have ever had. The countertops are magnificent. The deck is another room. Everything exceeds our wildest dreams.”

Bruce Nussbaum, BusinessWeek

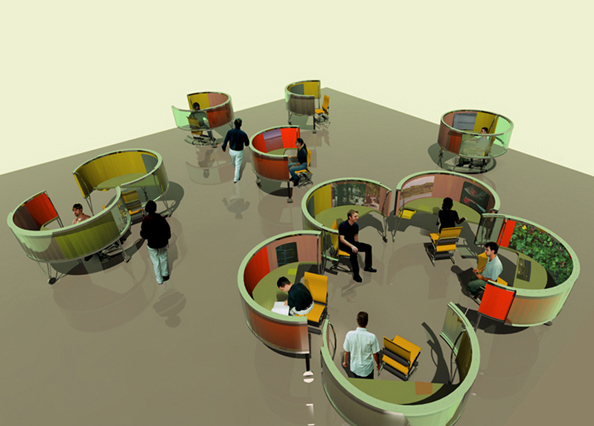

“In an era defined by people compulsively speed-dialing their cell phones and obsessively surfing the Net, Charles Rose…believe[s] that the best new ideas come from direct, human social relationships; quiet, private moments of epiphany; and serendipitous accidents of personal and intellectual collision and collusion. When technology makes any corporation virtual, the only justification for an actual building is to meet the human needs of the organization….In the architecture for the office of the future, everything is mutable. Nothing is fixed, not even the exterior skin of the office building, which changes with the weather….”

—”Offices that Spark Creativity,” BusinessWeek, August 21-28, 2000

Karen D. Stein, Architectural Record

“Gemini began this project as a means to develop a prototype for the firm’s 22 offices worldwide….The project reflects the company’s nomadic working method. There are few private offices or personal cubicles. Rooms are devoted to projects rather than personnel….’I rated this one fairly high,’ commented juror Frances Halsband, ‘because [the design team] has really gotten into designing special little places for specialized activities….They really have fitted the environment around the person.’”

—”Good Design is Good Business: Business Week/Architectural Record Awards,” Architectural Record, 1997

Craig Bradley, former Dean of Students, Kenyon College

“Charles Rose Architects understood the history of the college and of the campus, and their proposal to design the Woodland Cottages grew directly out of their clear understanding of our culture and traditions. They were also enormously responsive to our budgetary limitations, and I’m happy to report that the project came in under budget.”

Brian Carter and Annette Lecuyer

“The work of Charles Rose convincingly connects a concern with learning from the site and ideas of an architecture inspired by the details of its construction. That he has been able to synthesize those ideas beyond one locale to embrace dramatically different landscapes across the continent gives this work particular significance and authority.”

—All American: Innovation in American Architecture, Thames & Hudson, 2002

Steven M. L. Aronson, Architectural Digest

“Bell pointed to his violin—the storied 1713 Gibson Stradivarius—and encouraged the architect to take it as his source of inspiration (‘I paid about the same for my violin as for my apartment,’ he confides). Suggestion taken: The grille patterns in the cabinet doors resemble abstracted f-holes; the handrail to the roof apes the violin’s waist; and the apartment’s two dominating woods—reclaimed bubinga for the floors and and reclaimed wenge for the millwork—approximate the instrument’s aged maple, ebony and spruce.

Rose’s work is sculptural and lyrical. ‘In a lot of the forms here, the movement was inspired by Josh’s music,’ he recounts. ‘I often would draw in one room and he’d be practicing in the next.’ The top-floor ceiling does have a kind of undulation not unlike a melodic line—in fact, an incantation.”

—“Joshua Bell: Orchestrating a Penthouse in New York for the Virtuoso Violinist,” Architectural Digest, May 2010